They were sent into orbit to measure the Earth’s invisible magnetic field.

But a cluster of scientific satellites have been suffering mysterious blackouts as they circle the planet.

Scientists were left puzzled about why the three satellites launched by the European Space Agency have regularly lost their navigation signal when passing over the equator above the Atlantic Ocean.

Now they believe they may have uncovered the underlying cause of the strange loss in the GPS signal that helps control the satellites – thunderstorms high in the ionosphere.

Professor Claudia Stolle, from the German Research Centre for Geosciences in Postdam, Germany, said the storms can cause the signal to the Swarm satellites to vanish for several minutes at a time.

She said: ‘These ionospheric thunderstorms are well known, but it’s only now we have been able to show a direct link between them and the loss of the GPS.

‘This is possible because the Swarm satellites provide high resolution observations of both phenomena at one spacecraft.’

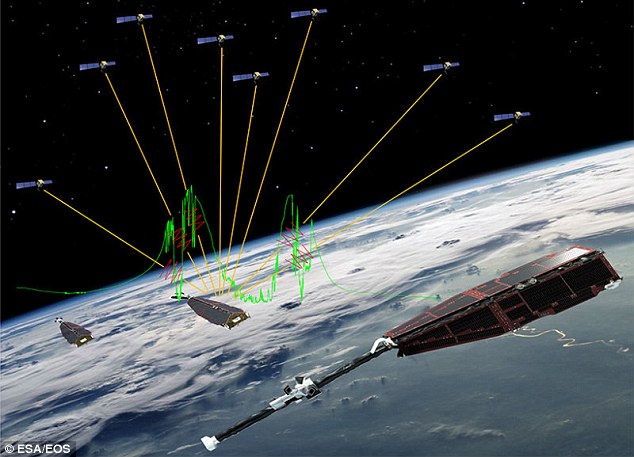

The Swarm constellation was designed to monitor the magnetic field that envelopes the Earth and to look for electric currents in the planet’s atmosphere.

They were launched in November 2013 with two of the satellites being sent to orbit side-by-side at an altitude of 285 miles and a third orbiting at 329 miles.

The satellites use GPS signals to help determine their precise position and timing as they orbit.

Yet as the satellites passed over the equator between Africa and South America they seemed to lose the GPS signal for several minutes.

GPS is provided by a suite of 24 satellites orbiting some 12,550 miles above the surface. They provide the signal that is used by satellite navigation systems, mobile phones, aircraft and many other devices here on Earth.

Researchers, whose work is published in the journal Space Weather, found that ionospheric thunderstorms appear to be able to disrupt these signals.

WHAT ARE IONOSPHERIC THUNDERSTORMS?

The lightning most of us are familiar with are the flashes of electrical discharge that fork down from thunderclouds or create bright sheets that momentarily light up the sky.

However, higher in the atmosphere short lived electrical activity can create other forms of rarely seen lightning.

The most common of these are sprites – flashes of bright red light – which occur high above thunderstorm clouds at up to 56 miles above the Earth’s surface.

Blue jets can also project from the top of thunderstorm clouds in a narrow cone around 30 miles above the Earth surface.

Occasionally dim flattened glows known as ELVES expand in diameter over the course of a millisecond occur around 62 miles up in the atmosphere.

Higher in the ionosphere the electrical discharge takes on the appearance of turbulence that creates bubbles in the electrically charged gases that occur at high altitudes.

Occurring around 186 miles to 372 miles up in the atmosphere, thunderstorms in the ionosphere are actually quite different from the lightning we see here on Earth.

Sunlight is so powerful at this altitude that it can strip the electrons from atoms, creating electrically charged particles called ions and free electrons.

Ionospheric thunderstorms occur as turbulence in these clouds of electrons which create small ‘bubbles’ inside which there is little electrically charged material.

These bubbles bend and scatter electromagnetic waves sent by GPS satellites 12,000 miles away, meaning the Swarm satellites are unable to pick up the signal.

Professor Stolle said the discovery promised to reveal new details about the electrical activity in the ionosphere and also learn more about how solar activity affects the Earth’s atmosphere.

‘It’s important to understand these external sources to get a complete picture of the Earth magnetic field,’ she said. ‘This study looks at one of these factors.’

The findings could also help to improve the reliability of GPS systems in the future.

Professor Stolle added: ‘The GPS has become a very convenient scientific tool for us in addition to being a navigation and positioning instrument for the satellite.’

By Richard Gray for MailOnline

Published: 05:37 EST, 4 October 2016 | Updated: 07:52 EST, 4 October 2016