Joplin’s corner of the country could be in line to be rid of an unsettling image. Ask an average American to describe our national landscape, east to west, and the answer might look something like this.

The ocean, small mountains, Tornado Alley, tall mountains, desert, the other ocean.

Now tornado researchers argue that the list should have another entry, at least for accuracy’s sake. So-called Dixie Alley, centered in Alabama and Tennessee, has seen a spike in tornadic activity over the last 30 years, even as Tornado Alley has seen fewer twisters.

The windswept phrase, which has been used to title a movie and a TV series, is more a product of culture than science. Tornado Alley is typically thought to include Texas, Oklahoma, Kansas and Nebraska, but Joplin, the site of the deadliest tornado in more than a half-century, is thought of as an honorary inductee.

Moving eastward

In January, a tornado plowed through a rural area south of Hoberg, 35 miles due east of Joplin, destroying some personal property and scaring the daylights out of residents, one of whom said that the EF1 twister sounded like a military jet flying low overhead.

Winter tornadoes are not uncommon, but they have a strange feel, perhaps because twisters hit more frequently in the spring. The one in Hoberg put Keith Stammer, emergency manager for Joplin, in mind of a shifting natural world.

“Storms have been progressively moving eastward for years,” Stammer said, referring to research that brings into question the traditional Tornado Alley.

Still, he said he hopes Joplin residents hold on to the label. National severe weather week is next month; emergency managers statewide are coordinating a tornado drill on March 6.

Even if Joplin sits a bit to the east of the traditional Tornado Alley — even if Tornado Alley is just a figment — he wouldn’t try to convince someone that they don’t live in Tornado Alley.

“I don’t really want to dissuade that thought,” he said. “I want people to be prepared.”

Dixie Alley

In a study published in 2016, Ernest Agee, of Purdue University, and several other scientists mapped tornado activity between 1984 and 2013, then compared it with the three prior decades.

They concluded that the center of tornado activity appears to be moving east.

Oklahoma saw a decrease in tornado activity during the more recent period, while Tennessee saw an increase.

Between 1954 and 1984, Oklahoma and Texas were the centers of tornado activity in the country. Over the subsequent three decades, the number of tornadoes there decreased.

During the same period, the zone with the most tornadoes, located in northern Alabama, the number of twisters jumped by roughly half, to 477.

Climate effects

Global climate warming — and our response to it, if any — remains a controversial matter in Congress. Sen. Jim Inhofe, R-Okla., drew the battle line in 2015 when he brought a snowball to the Senate floor as a reminder to his colleagues that, despite climate change, it still gets cold.

But behind those debates, which revolve around forward-looking policy decisions, is an undisputed fact. Looking back over the last 30 years, thermometers around the globe have measured higher temperatures, on average, than the three decades before.

By lining up the shift in tornado geography with a period of shifting global temperatures, Agee’s study suggests — but does not conclude — that the changes are related.

While scientists can say with confidence that climate change will lead to more severe floods and droughts worldwide, it could be years before tornado researchers make such a forecast.

Agee says his study established a geographical shift over time, but it does not prove that this shift is caused by climate change.

There are two key ingredients in tornado formation, and temperature alone is not one of them. First, winds at different levels of the atmosphere misalign, setting the stage for a vortex. Then parcels of warm air are pushed upward into the atmosphere, generating the energy that powers the storms.

Current models of Earth’s future climate predict less of the first ingredient and more of the second, Agee said. He noted one of those would imply more severe storms., and the other less severe storms.

Until those models are refined, he said, “we won’t know which is the likelier outcome.”

Research boom

Indeed, Agee says that his research shouldn’t even be used to predict the tornado season that begins next month.

In the context of a decadeslong shift in Earth’s climate, Inhofe’s snowball, an individual EF5 tornado and even a season’s worth of American tornadoes don’t prove anything on their own. Individual data points can tell us as much about climate trends as a single printed letter can tell us about the contents of a book.

But scientists are marshaling decades of data to strengthen their conclusions.

Though less frequent than tornadoes — and less damaging overall, by some measures — individual hurricanes can cause destruction on a far greater scale, and they have been the focus of most severe weather research as a result.

However, tornado research is catching up. Progress in the field has accelerated in recent years, spurred in part by the Joplin tornado, which brought attention to the issue and yielded much new data.

Untangling the impact of global warming on tornadic activity is the aim of Agee’s new research, which will use more detailed data to address one key piece of the puzzle.

“It is an exciting area of study,” he said.

A study authored by Agee and his students at Purdue, scheduled for release during the coming year, uses meteorological information linked to precise times and places over the past 39 years, allowing them to develop a sharper explanation for the increase in tornadic activity in Dixie Alley.

Agee hopes that our knowledge of tornadoes is changing faster than tornado season itself.

For now, he said, that seems to be the case: “Joplin can still expect an unsettling spring tornado season.”

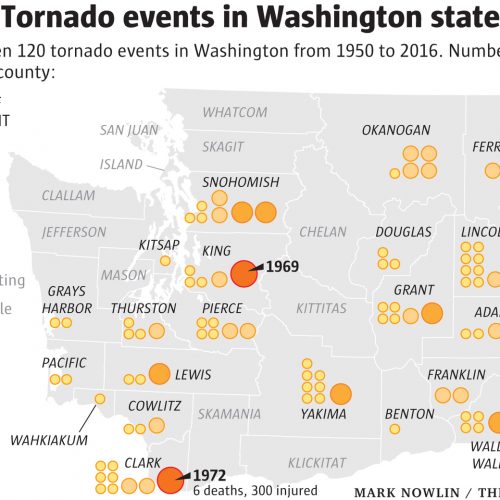

Trending to east

“Storms have been progressively moving eastward for years”, said Keith Stammer, Joplin-Jasper County emergency management director, referring to research that brings into question the traditional Tornado Alley.

by Koby Levin

February 18, 2018