Over the past decade, scientific understanding of tornadoes has improved, and the technology available to detect them has leapt forward. Yet recent statistics show National Weather Service forecasters are providing less advance notice for tornadoes than they did five years ago and more frequently failing to detect them.

The reasons for the troubling decline in tornado warning performance are complex and have confounded researchers. But experts reject the idea that forecasters have become less skilled at predicting tornadoes. “I’m sure they’re not getting worse,” said Harold Brooks, a senior scientist at the National Severe Storms Laboratory in Norman, Okla., which is part of the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. “They may be getting better.”

Brooks says the change in forecaster performance may reflect a change in decision-making psychology rather than declining forecast ability. He said forecasters have faced increased pressure from within the Weather Service to reduce tornado “false alarms.” Lest they cry wolf, he said, forecasters are predicting fewer tornadoes, but — as a result — are missing some in the process.

The data shows some support for Brooks’s hypothesis.

As background, the Weather Service evaluates how well it predicts tornadoes using three measures: lead time, probability of detection and the false alarm rate.

-Lead time refers to the amount of warning time, in minutes, before a tornado strikes.

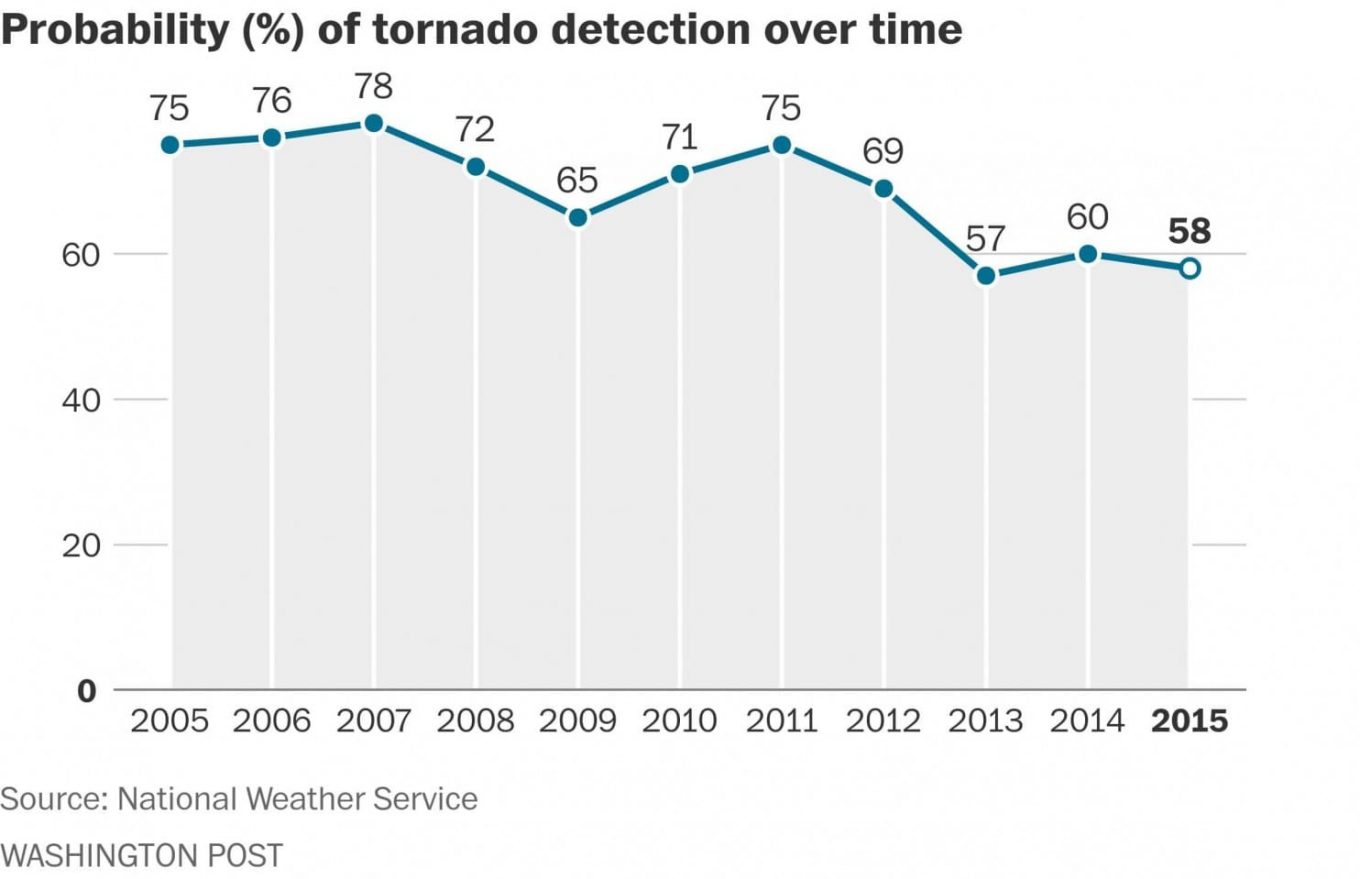

-The probability of detection expresses, as a percentage, how frequently warnings are correctly issued for tornadoes that are confirmed. For example, if four tornadoes occurred, and warnings were issued for three of them, the probability of detection would be 75 percent.

-The false alarm rate describes how frequently, as a percentage, tornado warnings are declared when no tornadoes occur.

Since around 2011, both tornado lead time and detection have gotten worse. But the false alarm rate has improved (decreased).

Between the fiscal (October to September) years of 2005 and 2011, Americans typically received 13 and 15 minutes of warning lead time before a tornado struck. But as of 2015, the lead time had dropped to eight minutes. This is well below the Weather Service’s performance goal of 13 minutes.

Note that these numbers are national averages and can vary substantially from region to region.

As the tornado warning lead time has shrunk, forecasters have also increasingly failed to issue warnings for tornadoes that have occurred.

Between 2005 and 2011, Weather Service forecasters detected between 65 and 75 percent of tornadoes. But that number plunged to 58 percent in 2015. Consider the Weather Service’s goal for detection is set at 72 percent.

The declines in tornado lead time and detection, on their own, might be concerning. But, at the same time, forecasters have more successfully resisted pulling the trigger when warnings are unnecessary.

About a decade ago, the tornado false alarm rate was about 80 percent. This meant for every five tornado warnings issued, only one tornado would occur. This false alarm percentage has since dropped to 70 percent.

In sum, it appears Weather Service forecasters are not preparing people for tornadoes as well as they did five years ago, but also are not needlessly warning them as much.

Brooks says these two developments are related and tied to what’s going on inside the forecaster’s head when forced with the stressful decision of whether to issue a warning.

In recent years, Brooks said, the Weather Service has placed “increased emphasis” on reducing false alarm rates, which may be motivating some forecasters to issue fewer warnings. Brooks referred to “unofficial efforts,” not policy, within the agency to curb false alarm frequency.

Greg Schoor, severe weather program coordinator at the Weather Service, confirmed its forecasters “have increased their focus” in reducing false alarm rates.

“I’m agnostic to whether that’s a positive,” Brooks said, stressing that he does not work for the Weather Service and that this view is his alone.

Forecasters try to avoid false alarms because conventional wisdom says that the public will ignore future warnings if they think previous warnings were busts, a problem known as “warning fatigue.” But Brooks explained that social scientists are only beginning to understand the implications of false alarms on human behavior and that such research is difficult to conduct and often inconclusive.

[Is a high false alarm rate for tornadoes cause for alarm?]

So it is unresolved whether it is better to warn more, miss fewer tornadoes and have more false alarms, or warn less, miss more tornadoes and have fewer false alarms.

Brooks emphasized that the Weather Service’s push for fewer false alarms cannot, by itself, explain all of the recent decrease in tornado lead times. The decrease may also reflect procedural changes in the warning process. In 2012, he said, the typical length of tornado warnings issued by the Weather Service was shortened from 45 minutes to 30 minutes. “If your warning is only 30 minutes long, you’ll never have a 31-minute lead time,” he said, which would mathematically reduce the average lead time — and potentially bias that performance statistic on the low side.

Additional possible causes for the decline in tornado warning performance measures were raised by researchers outside the government and the Weather Service itself.

Victor Gensini, a professor of meteorology at the College of DuPage in Glen Ellyn, Ill., who publishes tornado research, posited that in recent years there has been a relative lull in violently rotating thunderstorms, known as supercells, that frequently produce unmistakable signatures of tornadoes on radar. Such storms are often straightforward to issue warnings for but have been less prolific since 2012.

Instead, Gensini said, forecasters have been forced to play “whack-a-mole” with more subtle tornado signatures that form along thunderstorm squall lines, known as quasi-linear convective systems (QLCS). “They are impossible or difficult to warn for, because they can spin up within five minutes,” he said.

Karen Kosiba, a tornado researcher at the Center for Severe Weather Research in Boulder, Colo., said she was “surprised” by the declines in tornado warning performance and agreed efforts to try to warn for the fickle QLCS tornadoes could be contributing. “There’s a bigger focus in including those in the data space than there has been,” she said.

The Weather Service’s Schoor said data supports the conclusion drawn by Gensini and Kosiba that the downturn in tornado warning performance is related to the shift toward more of these hard-to-predict small, short-lived tornadoes. “Statistics over the past three years involve a smaller sample size of tornadoes dominated by these weaker cases and have likely contributed to the observed decrease in the scores,” he said. “Warning performance improves when well-predicted outbreaks occur with persistent, strong tornadoes.”

But Brooks isn’t convinced that shifts in storm behavior can explain recent tornado warning performance. He said tornado lead times have gone down just as much for strong tornadoes, which are typically easier to detect, as they have for weak tornadoes. “Lead times have dropped by three-four minutes at all [intensity] scales,” he said.

As researchers further debate the causes of the decline in tornado warning performance, Gensini said he would take a hard look at improving forecaster training. “I don’t think the way we train is optimal,” he said. “I see a lot of forecasters in Weather Service offices that don’t have the type of experience or training that I think would be necessary for issuing severe weather forecasts.”

Brooks said such training is ongoing. “New information is always being provided to forecasters,” he said. “Training for how to make warning decisions is constantly evolving.”

Meanwhile, a bold, new initiative has emerged to improve tornado prediction, part of comprehensive weather legislation signed by President Trump on Tuesday. It mandates a tornado warning improvement program with the aim of increasing tornado warning lead time to one hour — an ambitious goal considering the current lead time is closer to 10 minutes.

Both Gensini and Kosiba supported the spirit of the legislation but are skeptical such lead time increases are achievable.

[Congress passes comprehensive weather forecasting and research bill]

“I have no doubt they’ll be able to extend lead time,” Gensini said. “But the truth is there are going to be some circumstances that won’t lend themselves to long lead times. We’re still going to miss events.”

Fundamentally, Kosiba said, there is still much for the research community to learn about tornadoes to meaningfully improve warnings. “We really just need to better understand the small-scale precursors to tornadoes,” she said. “We’re still building the knowledge base.”

by Jason Samenow

April 20, 2017